Main Menu

- EnvironmentHealth

Main Menu

- EnvironmentHealth

The Tanzanian government has found it necessary to set up special centres to protect people with albinism who have had to flee their villages for fear of being butchered by traffickers in human bodies selling their limbs and organs to witch doctors to prepare their ‘prized’ good luck potions. However, the real killer they face every day is the sun, which consumes their lives, causing albinos to develop skin cancer before the age of thirty if they are not properly protected.

The Tanzanian government has found it necessary to set up special centres to protect people with albinism who have had to flee their villages for fear of being butchered by traffickers in human bodies selling their limbs and organs to witch doctors to prepare their ‘prized’ good luck potions. However, the real killer they face every day is the sun, which consumes their lives, causing albinos to develop skin cancer before the age of thirty if they are not properly protected.

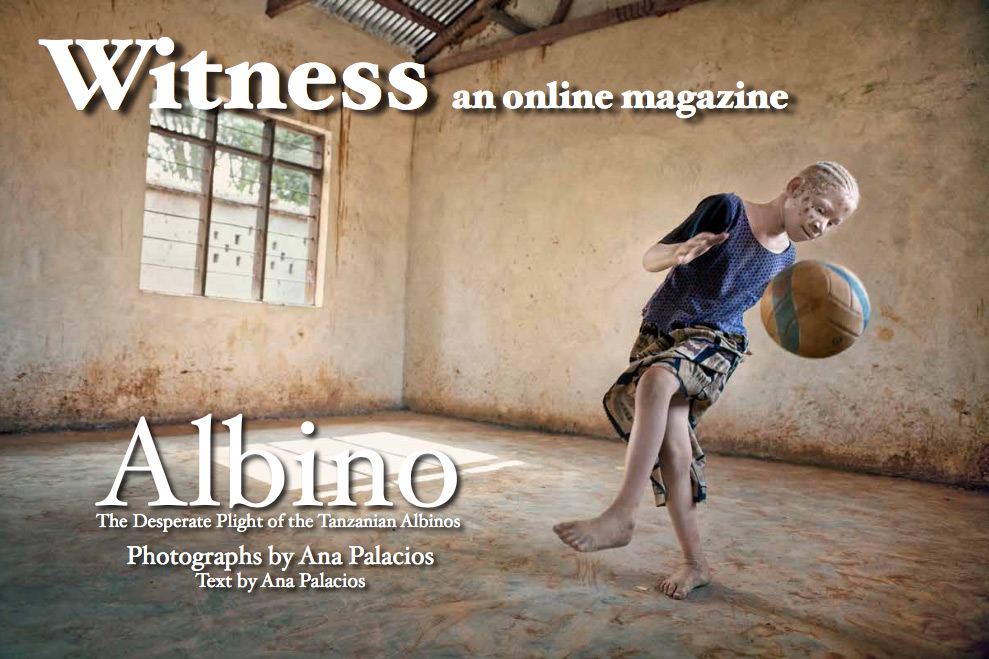

The first part of this project is a visual account of everyday life in the Kabanga refuge, where the Spanish NGO AIPC Pandora is engaged in a social work project to foster awareness and provide support to the albino community.

The second part describes the work of the Spanish doctors, health workers and pharmacists Spaniards in collaboration with local institutions in the Regional Dermatologic Training Centre (RDTC) at Moshi Hospital to combat both the discrimination and the skin cancer from which people with albinism suffer. They do this through prevention, promoting awareness, training and surgical interventions, supported by the NGO África Directo with direct actions such as contributing to the Kilisun project, which consists primarily in the sustainable manufacture of sunscreens for these people.

Tanzania is a country of forty million people belonging to more than a hundred different tribes and speaking a hundred and twenty seven languages. It is also a favourite destination for honeymooners eager to share the unforgettable experience of a safari in the Serengeti, snorkelling in the crystalline waters of Zanzibar and climbing Mount Kilimanjaro with a local guide. In fact, the largest albino community in Africa is concentrated on the slopes of Kilimanjaro.

In Kabanga, around a hundred albinos live alongside people with visual and auditory functional diversity. Many of them have had to flee from their homes for fear of being butchered simply for being people with albinism; others ended up here after being abandoned by their families, who were ashamed of them.

Albinism, which seems so exotic in the West, is a deadly serious matter for those who suffer from it in Africa. It is a genetic condition consisting in a lack of pigmentation in the skin, eyes and hair. It causes serious eyesight problems such as photophobia, strabismus, myopia and nystagmus (involuntary eye movements). An albino person’s skin has little or no melanin, which is a very effective blocker of solar radiation, and this makes them extremely vulnerable to the harsh effects of the sun. Without some other, artificial protection – sunscreen, long-sleeved clothing, sunglasses, hats, etc – from an early age albino children are very likely to suffer severe sunburn which can lead to skin cancer, or the eye damage that will leave them totally blind.

Aisha Adam is one of the lucky children at Kabanga because she lives with her mother and her three brothers. It’s one of the few cases of some kind of family group living at the centre.

Albino book + expo.

Photography and video

Ana Palacios

Witness – Albino. March, 2017

Stern – Albinos in Tanzania. January, 2017

Felista stitches countless school uniforms for the school closest to Kabanga. Along with selling produce from the vegetable plot, making these garments provides her only source of income.

Baswira Ntoteye shelters inside the huts at Kabanga to get away from the sun.

At Kabanga Center a hundred albinos live alongside another hundred people with a range of functional limitations such as visual and hearing impairment and mental problems.

Many women like Neema have to flee to complexes like Kabanga to seek protection when they give birth to an albino baby. The women who live at Kabanga take care of their own children and also act as “guardians” for other albino children who have been abandoned at the centre.

Genetics plays dice, and those unlucky enough to be born albino in Africa are doomed to lose the game. Skin cancer does not hurt, so albinos can be burned and begin to die without being aware that their life is in danger.

What is more, people with albinism in Africa are the victims of serious social discrimination. There is little awareness that albinism is a genetic condition. Many Africans don’t know why albinos are so similar in colour to their colonizers, and this ignorance creates myths and superstitions of all kinds. Some think they are the children of Lucifer, or that the mother had been with a white man; others believe they were conceived during menstruation, or that their condition is a form of divine punishment… A ‘white’ child is a stigma for the family: they are cared for less, given less to eat and educated less. In some tribes, indeed, albino children may be killed at birth, abandoned or offered for ritual sacrifice.

Many albinos are named Mavuto (‘problem’ in the Chewa language of Central Africa). This is just the first of a series of social disadvantages they will encounter in different stages of their life. Receiving little stimulus at home, they have difficulties in school because they can’t see the blackboard properly, and most fail to reach Secondary school, and are thus deprived of access to a decent job. It is hard for them to find a partner, since their condition as ‘damned’ beings scares others. Their own neighbours say that albinos do not die, they fade away, or that to touch one is to risk becoming white or falling ill. Living in such a social and cultural context is not conducive to self-esteem and some albinos experience the discrimination they are subjected to as natural; this is another reason why education and the fostering of awareness in these communities are so important.

BBC – On albino attacks. June, 2018

The daily routine at Kabanga gathers the women around the community kitchen to prepare their only meal of the day. On three days a week they have a piece of bread with their tea. The government provides basic food for this community every day so they can survive, as they can’t be self-sufficient with the produce they get from the centre’s vegetable plot.

The shortage of water at Kabanga is particularly alarming. When rainwater supplies run out they have to go to the hospital well to fetch water, with the black women taking turns so the albino girls don’t have to go out and risk being taunted or kidnapped.

Days Japan – Albino. November, 2016

Bath time starts at sunset in Kabanga. This is the safest time of day when albino children can take their clothes off without being afraid of getting their skin sunburnt.

Another danger has recently emerged to threaten these people: the so-called ‘albino elixir’ has become fashionable. It seems that in addition to traditional formulas, African witch doctors occasionally innovate with new formulas. In 2007 they began using albino body parts as ingredients in the concoctions they claimed would bring wealth and good fortune, and before long albinos were being murdered and dismembered to supply this macabre demand.

On the black market an albino arm can sell for as much as two thousand US dollars, a sum that in very poor countries can silence many consciences and make any neighbour a potential murderer. Sometimes, tempted by so much money, the albino’s own family may betray them to the traffickers.

In the last five years over one hundred albinos have been killed to feed the market in body parts, sowing the seeds of panic and triggering an exodus of albinos to from remote villages to big cities where they are less likely to be noticed or to centres like Kabanga, where the government provides police protection and they are safe.

Playing indoors keeps them away from damaging solar radiations.

Zawia speaks Swahili, English and sign language. She wants to be a teacher.

Albino book + expo.

Photography and video

Ana Palacios

Yo Dona – La maldición de los albinos en Tanzania (Albinos’ curse in Tanzania). August 2016

Ashura doesn’t have feet. In Kabanga, around a hundred albinos live alongside people with different physical issues, visual and auditory functional diversity and psychological problems.

The Kabanga centre, near Lake Tanganyika, in the west of the country, is a cheerful place, and home to some two hundred people. They eat, sleep, work the land, tend their own gardens, make their own clothes, run their own community kitchens and canteens, and have classrooms and play areas … but this lively village is actually a fortress which gives shelter to frightened people who have nowhere else to go.

In Kabanga, around a hundred albinos live alongside people with visual and auditory functional diversity and psychological problems. Genetic chance has made them exceptional beings and has brought them together here in order to survive. Many of them have had to flee from their homes for fear of being butchered simply for being albinos; others ended up here after being abandoned by their families, who were ashamed of them.

The Tanzanian Albino Society has registered eight thousand men, women and children with albinism. However, many more albinos – most of the people affected – are entirely unaware of the Society’s existence, while others prefer to hide. The Tanzanian Albino Charity has estimated that there are about one hundred thousand cases of albinism in Tanzania, which means that a great many people are still in emergency situations.

Without some other, artificial protection – sunscreen, long-sleeved clothing, sunglasses, hats, etc – from an early age albino children are very likely to suffer severe sunburn which can lead to skin cancer, or the eye damage that will leave them totally blind.

Lusia Josamu, who has the problems with nystagmus and poor vision typical of the genetic condition of albinism, tries to thread coloured beads onto fishing line.

An albino person’s skin has little or no melanin, which is a very effective blocker of solar radiation, and this makes them extremely vulnerable to the harsh effects of the sun.

Epafroida is always in a good mood. She takes pride in her appearance, loves fashion and wants to save some money so she can set up her own textile business in the market at Kasulu, the nearest village to Kabanga.

Bethod and Biko listen to Celine Dion on their old radio cassette player. They’re the oldest children at the centre. Men usually stay for a shorter time than women at these refuges and they try to form a family outside in the community.

Traditional games at Kabanga Center.

Zawia, wearing green clogs, and her friends finish school at five in the afternoon and go straight back to Kabanga, where they feel safer playing before a government cook serves dinner for everyone at six o-clock sharp in the communal dining-room.

Albino book + expo.

Photography and video

Ana Palacios

The area is due to provide a refuge for 50 more women in this albino bubble.

Eleven-year old Kelen loves dancing in the half-built bedrooms at Kabanga, away from the sun.

Lusia Josamu peers through cracks in the doorway separating the Kabanga refuge from the village.

At the same time, a team of concerned dermatologists, plastic surgeons, anaesthesiologists, pathologists and nurses, led by Dr Pedro Jaén, head of the dermatology department at Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, began to take an interest in this community. They knew that the albinos’ greatest enemy is the sun, because solar radiation causes thousands of deaths every year.

The team first visited Moshi to lend a hand in 2008, and every year since then this ‘life squad’ has come to the RDTC at Moshi Hospital in northern Tanzania to treat and operate on albinos with skin cancer. In these visits they have seen almost a thousand patients and saved countless lives.

In addition to operating on urgent cases, they run theoretical and practical workshops in dermatologic oncology and dermatopathology, thus making a valuable contribution to the training of the few dermatologists working in East Africa.

While the Spanish doctors were staying at the Regional Dermatology Training Centre in Moshi, the operating theatre was used every single second of the day and up to three patients were having surgery at any one time.

Since 2008, when this team of doctors started going out to Moshi, it’s estimated that their surgical skills have saved the lives of over 500 albinos.

Elmundo.es – Los guisantes Blancos de Mendel (Mendel’s White Peas). June 16th, 2013

After an injection of methotrexate, dermatologist Luis Ríos measures a tumour on Dada Molel, a 22-year-old Maasai woman from Arusha, to monitor her response to the treatment.

Dr Luis González injects the area to be operated on with local anaesthetics.

Getting a child to put on suncream, a hat and sunglasses every single day of his or her life is not easy. They may say they’ve put on cream when they haven’t, the hats get lost, the glasses get broken … Like most children anywhere, they find the whole thing a nuisance. The difference is that for these kids, if they don’t cover up they’re likely to die before the age of thirty, which is the life expectancy of a Tanzanian albino.

Another big problem is that a bottle of sunscreen costs as much as two chickens. You can feed ten people with two chickens. These simple figures from a Primary school arithmetic lesson explain why many people choose to eat rather than get sun protection, and why it was essential to distribute throughout the country free sunscreen, specially produced to meet the specific needs of people with albinism, and to make people aware of the vital importance of its constant use. This is the work in which the NGO África Directo and the pharmacist Mafalda Soto are immersed with the Kilisun project, in collaboration with the Tanzanian RDTC. In 2015, thirteen thousand bottles of suncream were distributed to more than two thousand three hundred people with albinism, reaching even the most remote areas of Tanzania, with the aim of reducing the incidence of skin cancer and improving people’s quality of life.

GEA Photowords – Albinos. Fantasmas de África (Albinism. Ghosts of Africa). November 5th, 2014

Handing out jars of Kilisun to children at Old Moshi Secondary School for their daily protection.

FronteraD – Atravesando lo invisible (Going through the Invisible). October 9th, 2014

Elpais.es – El refugio de los albinos (Albinos’ Shelter) January 9th, 2014

The Kilisun production laboratory, Kilimanjaro Sunscreen Production Unit, was opened in July 2013. In 2016 it distributes its products to two thousand three hundred people with albinism.

The Kilisun team consists of Mafalda Soto, director; Ebenezer Fabian, production; Sang’uti Olekuney, distribution and community work; and Grace Manyika, laboratory assistant.

Grace Manyika checks the jars before sending the product to the distribution centres.

Dr Ríos prepares an injection of methotrexate, a chemotherapy treatment he will apply to the squamous cell carcinoma that Dada Molel suffers in the right malar region.

Prevention and treatment are essential to avoid the physical damage suffered by the albino population, but they cannot solve the problem as a whole. They must be combined with the grassroots work of fostering awareness among non-albinos to help end the discrimination and violence inflicted on albinos. And getting rid of prejudice means education, starting in Primary schools. There is also an urgent need for forceful action by the justice system to end the impunity of the ‘hunters’. Improving the daily lives of albinos in Africa is a comprehensive project that can only be carried out by thinking for the long term and taking transversal actions. It requires the participation of primary and secondary actors, which means that the message must be spread through all possible channels.

One day, Zawia, a twelve-year-old albino girl living in Kabanga, began to take photographs with a little compact camera we had lent her. She learned to frame the shot, to think what she wanted to photograph and to evaluate her own work. When she had showed me the pictures she had taken, she looked at me, smiled and thanked me. As I was hugging her in delight, I realized that I was in an exceptionally privileged position and faced with a unique opportunity to practise this wonderful profession of photojournalism. This chance to show and tell who these people are and what is happening to them and to document the various aspects of this project has been a deeply moving experience.

It’s great to think that through my reports and exhibitions, and now with the book ALBINO, I can help draw attention to a little-known problem and in so doing get more people involved in the project. Because I would love Zawia to finish Secondary school and go on to become a teacher, and perhaps, one day, show me pictures of her children. And I’d like to express my deep gratitude to all of the people who have made these pages possible, and to you for reading them, because maybe that day is a little closer now.

Sang’uti Olekuney gives a demonstration of how to apply Kilisun correctly at a mobile clinic in Old Moshi Secondary School.

Daudi Mavura, director of the RDTC, and Rodgers Nonde, a second year house officer, apply cryotherapy to precancerous lesions on Furaha Machibya, an 18-year-old patient.

Before excising a tumour, Dr Carmen Carranza gives a shot of anaesthestic to Joseph Teciete, a 33-year-old patient from Kidubula.

Dr Jesús Cuevas, a dermopathology specialist, shows a sample of histoplasmosis in a patient with HIV under the microscope to Dr Emmaneli Moshi, head of the Pathology Department at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam.

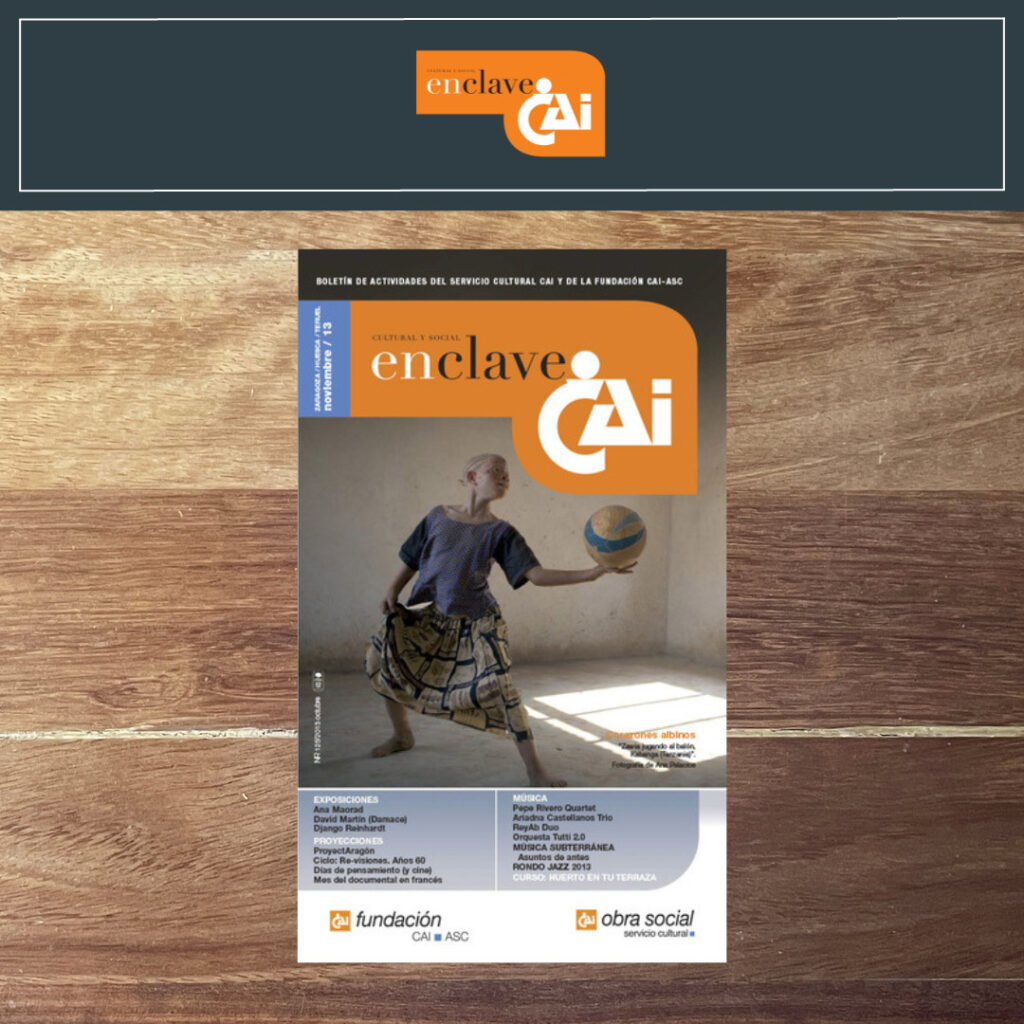

Enclave Magazine. November 2013

In the waiting room at Moshi Hospital, patients with albinism have access to educational brochures that give them a clearer understanding of their particular genetic condition.

Albino

Photography

Ana Palacios

If you have made it this far and you enjoyed it, you should know there is an exhibition available of this project.

Please, feel free to contact me@ana-palacios.com for further details.

Anónimo es nombre de mujer. Mujeres fotógrafas en la Colección Alcobendas

Collective exhibition. Centro de Arte de Alcobendas.

La habitación de juegos

Galería Luis Burgos. PhotoEspaña. Madrid.

Showcase

EFTI. Madrid

Creadores de Conciencia

Collective exhibition. Cultural Center La Asunción at the Photo Festival Miradas. Albacete.

Book selling

Visa pour l’Image festival. Perpignan.

Cinco miradas, cinco fotógrafas

Collective exhibition. Cultural House Teodoro Cuesta. Mieres, Asturias.

Creadores de Conciencia

Collective exhibition. Museo Barjola. Gijón.

Creadores de Conciencia

Collective exhibition. La Lonja. Zaragoza.

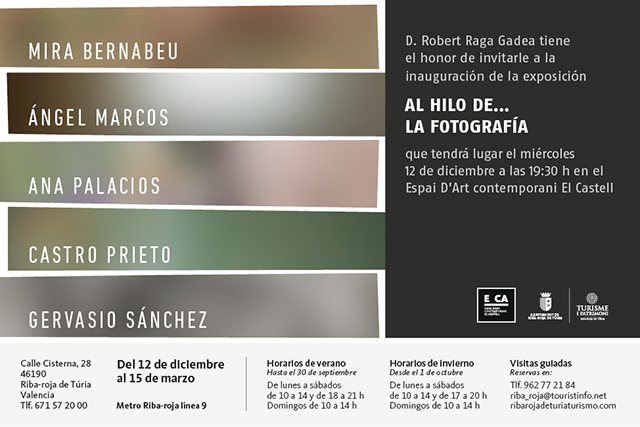

Al hilo de la fotografía

Espai d’Art Contemporani El Castell de Riba-roja del Túria. Collective exhibition. Valencia.

Albino

CAM Alicante.

Paraty em Foco Festival Internacional de Fotografia

Collective exhibition. Paraty (Brasil).

Iguales en Derechos. Abogacía por la Igualdad

Collective exhibition. Muelle Calderón. Santander.

Albino

Mandarin Oriental Hotel. Collective exhibition. Kuala Lumpur (Malasia).

Albino

Museum of Sydney. “Head On” Portrait Prize exhibition screening. Collective exhibition. Sydney (Australia).

Albino

Centro de Iniciativas Culturales, Universidad de Sevilla. Sevilla.

Albino

Visa pour l’Image festival. Collective exhibition. Perpignan

Albino

Alliance Française. Madrid.

Planet in Positive

Collective exhibition. Stories Center. Zaragoza.