Main Menu

- EnvironmentHealth

Main Menu

- EnvironmentHealth

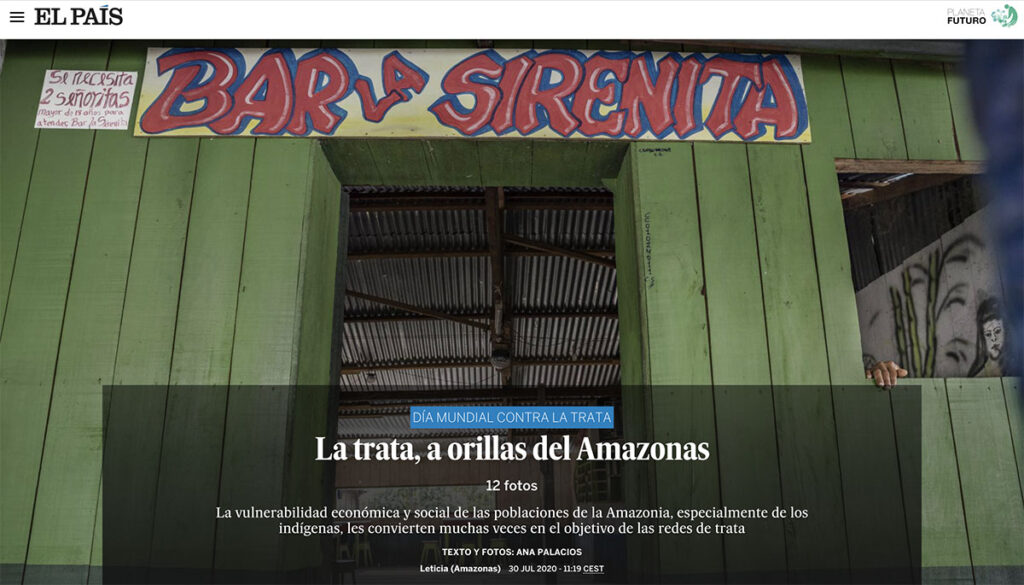

“Sexual exploitation and slave labor are two forms of human trafficking that we’ve identified in these communities in the Amazon. Trafficking networks are well aware of the vulnerable state of young people in this territory. They know that many of them cannot find any other alternative in their communities and that, in the best of cases, they’ll finish school only to encounter barriers to continuing their studies and direct their lives towards a long-term project. This isn’t forced or obligatory recruitment, instead it is subtly disguised as a ‘patronage’ and dressed up as opportunities, oftentimes even with the family’s consent, although the family is unaware of the full scope of what this entails. These situations are legitimized, naturalized, and excused.” Nathalia Forero Romero. Coordinator of the Defenders of Life Network and a member of the Network to Confront Human Trafficking in the Triple Border.

Girls studying in the hallways of the San Francisco de Loretoyaco Indigenous Boarding School Puerto Nariño. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

The fortress that is the Amazon is being attacked from so many fronts that it starting to grow weak and turning into a fragile territory on the brink of death.

The indigenous leaders on the triple border between Peru, Brazil, and Colombia —an area deep in the heart of Amazonia made especially vulnerable by its geographical location on the border— are fighting and raising their voices to denounce the perils currently suffocating the world’s biggest tropical rainforest.

The tragic fires in Brazil and the various climate summits have put the media spotlight on the critical situation in this geographical area that plays a strategic role in regulating our climate and ensuring the planet’s survival.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg of the crisis situation in a complex territory with many other open wounds where women are especially vulnerable to having their basic rights virulently violated.

Caballococha, a small Peruvian town on the shores of the Amazon, is one of the usual leisure destinations for coca lords and illegal loggers. Lax policing in the area and along the river give way to the sex trafficking of young people from neighbouring countries.

View of the Amazon riverbank from Caballococha. Caballococha. Department of Loreto. Peru.

Kitchen in a village house. San Francisco. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“It is estimated that there are 102 indigenous peoples in Colombia. According to the Colombian Constitutional Court, 36 peoples are at risk of physical and cultural extinction due to direct consequences of the armed conflict and another 31 peoples are in a process of complete disappearance due to their low population growth among other causes.” María Carlina Tez, Coordinator of the Truth Commission Macroamazonía. Colombia.

Home of the family Durango. Monilla Amena. Resguardo Tikuna-Huitoto. Leticia. Department Amazonas. Colombia

The Kulina, Marubos, Kanamari and Mayoruna peoples who live in the Javari Valley, come to the municipality of Atalaia do Norte, in the Brazilian Amazon, for medical emergencies.

Indigenous famlies on their boats at the riverbank at Atalaia do Norte. State of Amazonas. BraziL

“The world has to look after the Amazon because it is our Common Home. It has to inject money in this area in order to protect the environment. Governments have to guarantee whatever is necessary to protect indigenous peoples, their cultures, and their territories, biodiversity, and social diversity. If its inhabitants are lacking economic opportunities, they will continue to deteriorate the environment at the service of logging companies or drug trafficking in order to survive and avoid being forced to migrate. But if they are offered a means of subsistence, they will behave responsibly and protect the territory, respecting the rights of people and of the earth based on a worldview that is inherent in their tradition.” Edelmira Pinto. Coordinator of the San Francisco de Loretoyaco Indigenous Boarding School Puerto Nariño. Departament of Amazonas. Colombia.

Aryana Adali bathing in the Tacana River at the Monilla Amena Community. Monilla Amena. Resguardo Tikuna-Huitoto. Leticia. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

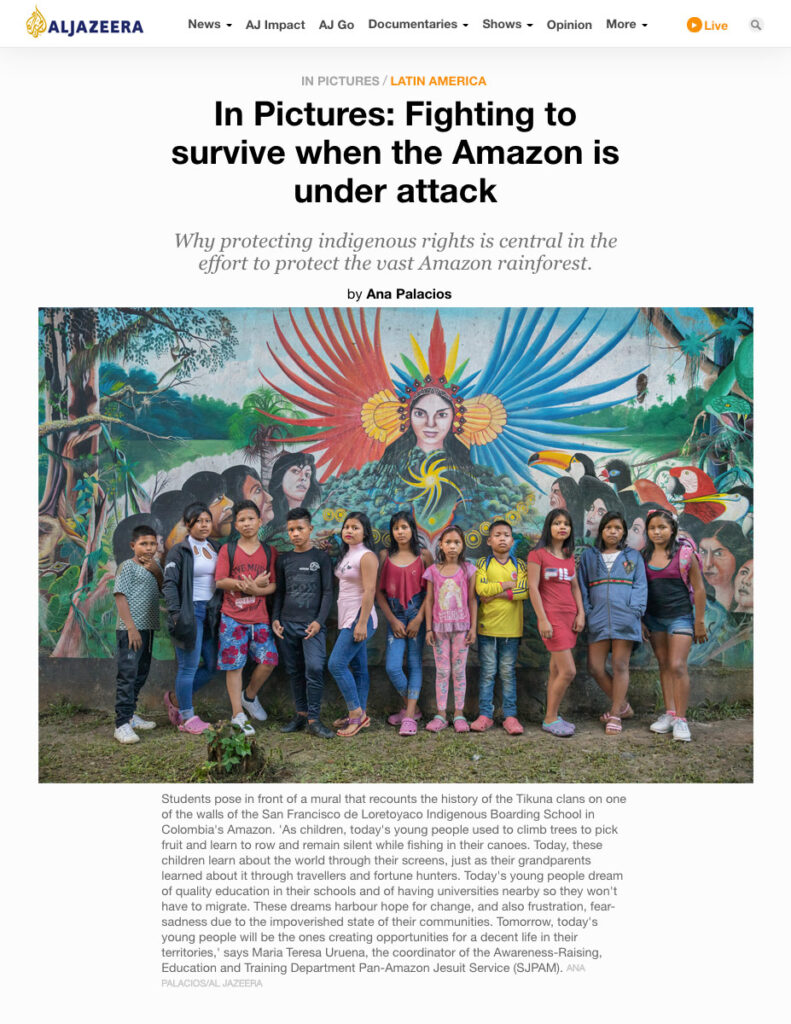

Al Jazeera – Fighting to survive when the Amazon is under attack. December, 2019

“Most of the 64 indigenous peoples of the Colombian Amazon are in high risk of physical and cultural extinction due to the armed confict. The Truth Commission is to identify patterns of violence in this territory being the forced recruitment of children and sexual violence against women the most frequent ones.” Jorge Pulecio. Regional Delegate of the Truth Commission Macroamazonía. Colombia.

Juliana Yucuna, age 9, playing in the dining hall at the Monilla Amena Community. Monilla Amena. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“The world has to look after the Amazon because it is our Common Home. It has to inject money in this area in order to protect the environment. Governments have to guarantee whatever is necessary to protect indigenous peoples, their cultures, and their territories, biodiversity, and social diversity. If its inhabitants are lacking economic opportunities, they will continue to deteriorate the environment at the service of logging companies or drug trafficking in order to survive and avoid being forced to migrate. But if they are offered a means of subsistence, they will behave responsibly and protect the territory, respecting the rights of people and of the earth based on a worldview that is inherent in their tradition,” says Edelmira Pinto, coordinator of the San Francisco de Loretoyaco Indigenous Boarding School Puerto Nariño.

Indigenous traditions painted on the wall of a house at Puerto Nariño. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

Caption Magazine – La Amazonía Silenciada. March 2021

“As children, today’s young people used to climb trees to pick fruit and learn to row and remain silent while fishing in their canoes. Today, these children learn about the world through their screens, just as their grandparents learned about it through travelers and fortune hunters. Today’s young people dream of quality education in their schools and of having universities nearby so they won’t have to migrate. These dreams harbor hope for change, and also frustration, fear sadness due to the impoverished state of their communities. Tomorrow, today’s young people will be the ones creating opportunities for a decent life in their territories.” María Teresa Urueña. Coordinator, Awareness-Raising, Education and Training Department Pan-Amazon Jesuit Service (SJPAM).

Diosjhaimer, a 7th-grade student, poses in front of a mural that recounts the history of the Tikuna clans on one of the walls of the San Francisco de Loretoyaco Indigenous Boarding School. Puerto Nariño. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“Our job is to teach indigenous women about their rights, to food sovereignty, healthy food, and enjoyment of their economic, social, and cultural rights. We train them to incorporate objectives aimed at preserving their culture and natural resources in their projects from the perspective of integral ecology. Training these women is a way to start raising awareness among families, ensuring that indigenous families respect children’s right to life.”

Fany Kuiru Castro. Women, Children, Youth, and Family Coordinator at the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC)

Fany Kuiru Castro at home with her pets Frank, Jazukītoī, and Sophie. Bogota. Colombia

“The role of indigenous women is compromised because they are caught in the ambiguity of so-called ‘development.’ The struggle of indigenous women is invisibilized; it has been silenced by the conflict. Educational policies tend to be militaristic, focused on the world of capitalist labor and the slavery of the other (companies, NGOs, etc.). They take over young people’s time and space without allowing them to quietly enjoy the rhythm of life. This produces agronomists who have no desire to try to understand the productive dynamics of indigenous peoples. It is an obsolete pedagogy that is boxed into a limited space, forgetting that the learning process for boys, girls, and teenagers is diverse and involves people of different generations.” Anitalia Pijachi Kuyuedo. Ocaina-UItoto or Murui Indigenous Leader of the Janayari (“Jaguar”) Clan. Graduate in Ethno-Education. Member of the Truth Commission. Leticia, Colombia.

Rihanna in her classroom at the José Antonio Galán Educational Institution in San Francisco. San Francisco. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

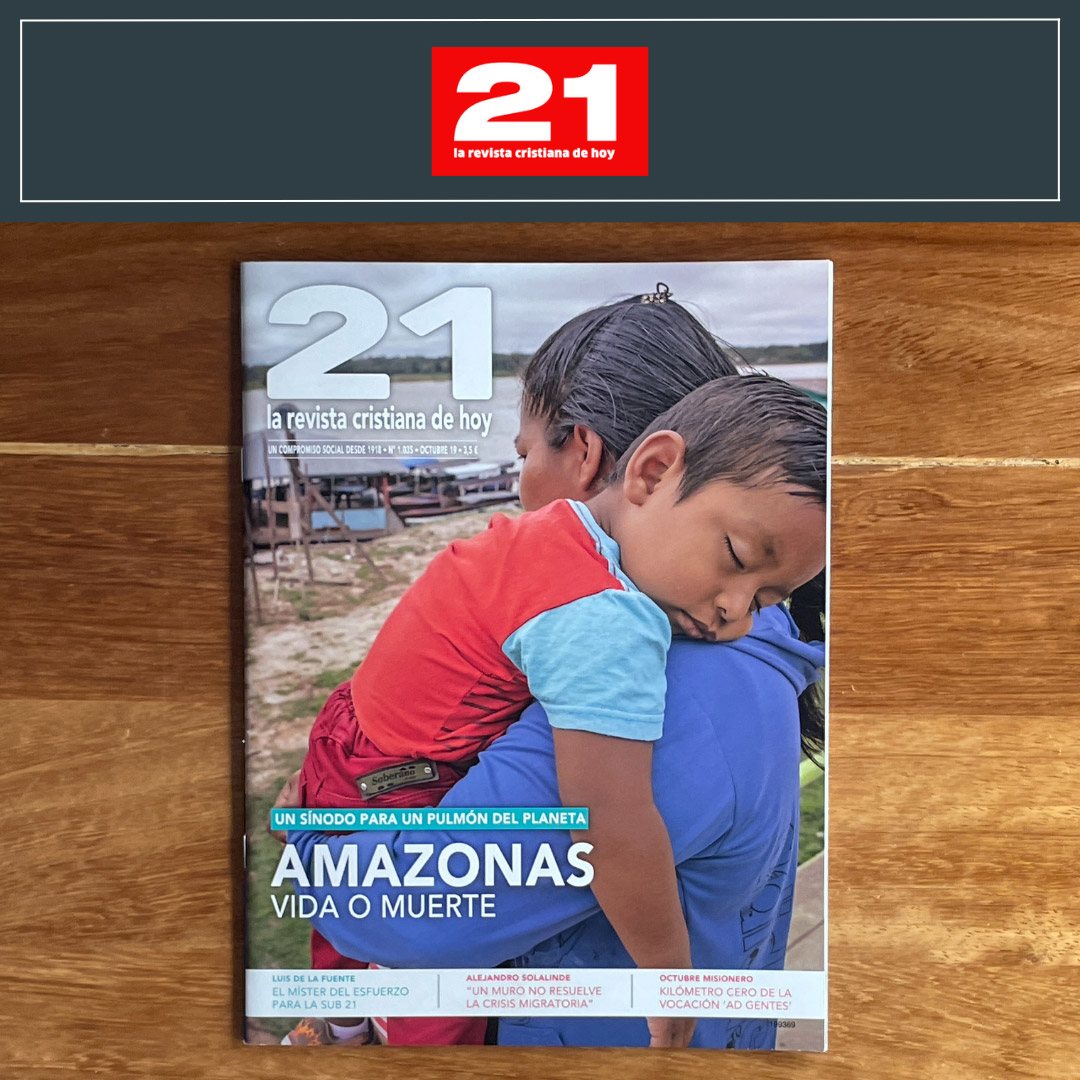

21 La Revista Cristiana de Hoy – Amazonas Vida o Muerte. October 2019

Indigenous peoples constitute 5% of the world’s population, but they manage a third of the Earth’s forests and serve as caretakers for 80% of the biodiversity on the planet (according to the FAO). For centuries, they have protected Amazonia, respecting and venerating “Mother Earth”.

Today, the rights of these indigenous peoples are being compromised by the economic interests of the extractive industries that are rapidly expanding in Amazonia under the cover of institutional policies that neglect these communities and serve to foster violence.

“Everything is sustainable in this farm. There is no waste. If there is excess harvest, in Puerto Nariño they do not buy it from us, what we do is conserve, what could not be consumed is given to the animals. Here diversity is maintained. We respect the spaces between each tree.” Vilma, farmer.

Vilma, a worker at the Abijan Fernandez farm property. San Francisco. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“It’s entitled ‘The Jungle is Dying.’ I tried to distinguish between two spaces, the one on the right is where there’s pollution, with the chainsaw, the ax, contamination from the poisons used to kill plants and insects, factories, oil companies… The cranes are felling trees, we see oil spills, garbage… All governments think of is making a profit, they think the jungle is full of money. That’s why we have those things called ‘dollars’ or ‘Washingtons.’ It’s a way of symbolizing the indigenous struggle against the depredation perpetrated by governments.” Santiago Yahuarcani. Painter and Sculptor. Leader of the Murui and Bora People on the Ampiyacú River.

The painter Santiago Yahuarcani shows his work “The Amazon Jungle is Dying”. Caballococha. Department of Amazonas. Peru

Out of 34 million people living in this territory, three million are indigenous people, suffering serious human rights violations, specially children and women, being the most vulnerable and unprotected groups, object of human trafficking, drug dealing, work exploitation, lack of education and health services on their communities, recruited for armed conflicts, etc.

The “maloca” is our healing center. Here all the sick will be cured through our sacred plants, tobacco, sweet yucca and coca. Unfortunately, among the non-indigenous population, coca is understood as the raw material to transform it into cocaine for the international market. Working on these crops, processing or selling it is not recognized as a problem because it is a source of employment and income for the population. We have whole families that go two or three months inside the jungle to scrape the coca and that implies that they leave the house in the forest, fishing … modifying the indigenous traditions and altering the cycles of this ecosystem.” Elver Isidio Viena. Captain of the Monilla Amena community.

Ritual preparation of tobacco and coca. Akile and Alonso Arango, of the Murui People Monilla Amena. Resguardo Tikuna-Huitoto. Leticia. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“We use coca, sweet cassava, and tobacco to manage pain. When we feel weak or sick, we connect with God Almighty through these offerings. We invoke the spirit of God and the spirits of our ancestors so that they will show us the way, give us strength and help us get up. This is how we cope with pain and conquer it. For us, coca is a sacred plant; the use of this plant by Westerners is drug trafficking. Coca is meant to be used to work and to cure. It is not a vice. It is part of our spirituality.” Juan Enocaisa Guidone. Teacher and Indigenous Leader of the Murui People at the “El Estrecho” Community, Guepí Reservation, Teniente Manuel Clavero District, Department of Alto Putumayo, Peru.

Ritual preparation of tobacco and coca. Akile Arango, of the Murui People. Monilla Amena. Resguardo Tikuna-Huitoto. Leticia. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

“The indigenous traditional medicine nourish from the plants of the jungle. Mainly, we use the tobacco as a healing plant, we prepare ointments and drinks like the Anyiroba for rheumatism, Agua Florida to scare away evil spirits, Chuchuwasa for the muscles pain and Ayahuasca we use for clean the soul and you, westerners, use it to fly away.” Mamerto Caguache. Cocama People Shaman.

Nazareth village house. Meeting point for traditional doctors. Resguardo indígena de Nazareth. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

El País – La trata, a orillas del Amazonas. July 2020

Deforestation, changes in land use, intensive agriculture, river pollution, human trafficking, drug trafficking, and large-scale fishing are just some of the challenges the territory is facing. Indigenous leaders are fighting against these series of abusive situations even to the extreme of being killed.

“We plant to consume and also to feed the soil, which also has to eat. You have to pay a part to the ground and nature, for birds, monkeys … ” Patricia Calderón. Yukuna leader and Captain`s wife in the Monilla Amena Community.

Chicken to be prepared by Tatiana with rice and cocona juice in the kitchen of the Monilla Amena Community. Monilla Amena. Departament Amazonas. Colombia

“We rarely go to the hospital because everything is in here, in nature, for fever, stomach problems … everything is here. For example, for family planning we use avocado bush, yellow leaves, wash and cook those leaves, when it gets the red color, you take that drink during the 5 or 6 days that you are with the period. It works.” Patricia Calderón. Yukuna leader and Captain`s wife in the Monilla Amena Community.

Patricia and her daughter-in-law, Tatiana prepare chicken with rice and cocona juice in the kitchen of the Monilla Amena Community. Monilla Amena. Departament Amazonas. Colombia

“For years, we have been suffering the assaults of intruders in our valley. We have been invaded by logging companies that are destroying nature, unscrupulous gold diggers, and illegal hunters who are depleting stocks. We respect the cycle of life and they don’t; they’re destroying everything. Oil companies have no respect for the earth, and they’re polluting our rivers, thus damaging the health of its inhabitants. This is not just affecting the valley, it is affecting the entire Amazon and the planet because this is everyone’s home. Bolsonaro’s government is annihilating us, and that’s why it’s important to speak out so that people know what is happening to the indigenous peoples of Brazil and take some sort of action.” Andrés Wadick. Indigenous Leader of the Mayoruna People.

Andrés Wadick at home with his grandson Asafi, his brother-in-law Pereira, and his nephew Orlando. Atalaia do Norte. State of Amazonas. Brazil

Amazon’s natural riches are the object of greed worldwide, sometimes even denying the scientific evidence that warns of a “point of no return” in the deterioration of quality of life on the planet.

Indigenous peoples constitute 5% of the world’s population, but they manage a third of the Earth’s forests and serve as caretakers for 80% of the biodiversity on the planet (according to the FAO). For centuries, they have protected Amazonia, respecting and venerating “Mother Earth”. Today, the rights of these indigenous peoples are being compromised by the economic interests of the extractive industries that are rapidly expanding in Amazonia under the cover of institutional policies that neglect these communities and serve to foster violence.

Sawmill in Islandia. District of Yavarí. Perú

“The Pan-Amazon region is a source of life at the heart of the Church and the world. Their particular presence, spiritualities, eco-biodiversity, and beauty speak to us of the mystery of God’s creation. On the other hand, the throwaway culture model is threatening everything that sings life and hope in the region. It is time to act on behalf of life and hope”.

Mauricio López

Executive Secretary, REPAM

We need to promote positive policies like offering incentives for reforestation to small and large-scale farmers. This would allow us to promote sustainable agricultural practices. Even encouraging tourism helps protect the jungle. In the past, young people would go to the countryside to work in the ranches. Today some still do, but it’s not like it used to be. While they do have a stable food supply, consolidating tourism would create employment opportunities for young people. Unfortunately, without job opportunities, they’ll take any offer and end up getting lost in other worlds, like drug trafficking, selling their bodies…By creating jobs in the sustainable tourism industry that helps preserve the environment—mapping and promoting hiking trails or creating bird watching routes—we can prevent young people from resorting to these very detrimental alternative sources of livelihood”. Marco Antonio Guzmán Restrepo. Director of the Production Sector and Environment at the Municipal Unit of Technical Agricultural Assistance (UMATA) at Puerto Nariño’s Mayor’s Office. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

Children playing along the banks of the Igara Paraná River. San Francisco. Puerto Nariño. Department of Amazonas. Colombia

Fragile Amazon

Photography

Ana Palacios

If you have made it this far and you enjoyed it, you should know there is an exhibition available of this project.

Please, feel free to contact me@ana-palacios.com for further details.